The Henry Mountains at sunset

For over 300 years the curse of the Henry Mountains has persisted. Like many folk stories, the tale begins with greed and ends in ruination. Fact and fiction are woven together in this tale making it more legend than truth.

“To him who reopened the mines will some great calamity come,” wrote Edward T. Wolverton in his 1928 manuscript, Legends, Traditions and Early History of the Henry Mountains. “His blood will turn to water, and even in youth he will be as an old man, his squaws and papooses will die. And the earth will bring forth for him only poison weeds instead of corn. Various other punishments will attend to him; too numerous to mention.”

Wolverton built a mill and worked a mine at the base of the Henrys for years. His attributes the curse to a medicine man in the late 1700s.

For generations, the whisper of gold in the Henrys have been unrelenting. Explorer Silvestre Velez de Escalante first mapped the Henry Mountains, the closest range east of Capitol Reef National Park, in 1776 for Spain.

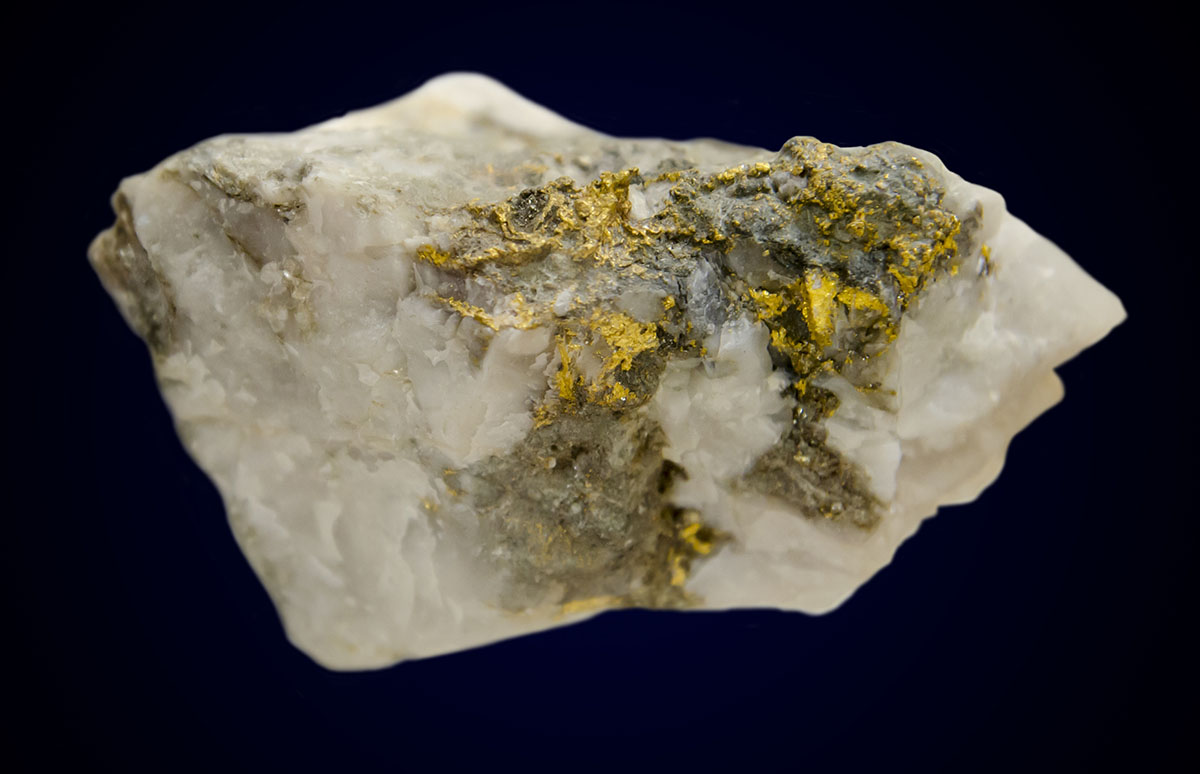

Years later, the Spanish mined the mountains for gold using the local Native Americans as their laborers. The Native Americans were forced to perform the back-breaking task of digging into the mountainside. Gold was extracted from the quartz within the mountain. The gold didn’t stay in the area. It was sent by way of the Old Spanish Trail to Mexico City and then on boats headed to the royal coffers of Spain.

For many years the Spaniards grew rich on the gold from the mines but that was about to end. One morning, some say it was in early spring, the surrounding hills were full of Native American warriors. Unhappy with their subjugation, the Native Americans fought the Spanish. Many lives were lost on both sides. When the battle was over, all the Spanish were dead. The entrances to the mines were destroyed or packed in with rocks. The curse was placed upon the mine and any person who would disturb the mine. That is where the legend ends.

The lore grew stronger as the pioneers settled the area and built homesteads. The people and places existed. Where coincidence and curse separate are still unclear 150 years later. There is some historical accuracy to the next part of the story.

In 1868, Ben Bowen ran a stage station where exhausted horses and riders could rest before continuing their journey. The station was located approximately 100 miles southeast of the Henry Mountains. Sometime after Bowen had purchased the stage station, a ravaged and sick man named Burke stopped by. Burke had been prospecting in the Henry Mountains but was run off by Native Americans. Most of his possessions, including all of his prospecting equipment were taken from him. His life was spared but he was ordered never to come back to the gold mine.

Burke had hidden a gold nugget and managed to escape with it. Burke told Bowen he had found the old Spanish mine and presented the gold as proof.

Ever an opportunist, Bowen saw a quick way to make money. He convinced Burke to stay at the stage station and upon his recovery become partners and start a gold mining outfit. Grateful for the help and wanting to continue prospecting, Burke agreed that he would be Bowen’s guide and partner.

Several months passed and Burke regained his health. Bowen and Burke secured an outfit. They stopped in a town on their way to the Henrys, and hired a man named Blackburn. His job was to tend to the outfit’s horses, cook and act as a guide.

The outfit camped about 50 miles from the base of the Henrys. Burke led Bowen and the outfit to the mine. They immediately found gold. The archives said Bowen and Burke broke off about 400 pounds of quartz with gold deposits running throughout. Eager to cash in on their find, the outfit dragged the quartz down the mountain and through Penn-Ellen pass back to town.

Their eagerness proved fateful. The outfit got lost among the canyons. Low on water and suffering from thirst, they found a small pool of water. Although Blackburn begged them not to, both Bowen and Burke drank heartily, and soon after were violently ill. They made it to the town where Burke and Bowen were cared for. Their condition improved, and they found out about the curse.

Blackburn believed every word of the curse and refused to continue the expedition. The gold ore was sent to Salt Lake City to sell for a tidy sum.

Bowen was still feeling the effects of the poisoned water, but the doctors could not do much for him. Bowen was convinced his illness was due to the old curse placed on the mines. He refused to go back with the outfit and returned home.

Burke had no plans to stop the venture. Burke insisted that the curse was irrational and was nonsense. He pointed out to Bowen that illness from bad water happened frequently to pioneers. Soon, Bowen’s greed overcame his fear and he left with Burke for more gold.

While waiting in Rabbit Valley, Bowen was stricken with a mysterious illness and died. Four days later Burke died. No one in the outfit continued the quest.

Blackburn lived but faced calamity throughout his life saying that sickness in his family and bad luck followed him for 30 years.

Find out where lore ends, and fact begins at Capitolreefcountry.com.

Keep Capitol Reef Country Forever Mighty

What is Forever Mighty? It’s practicing responsible travel while visiting Utah and Capitol Reef Country by following the principles of Tread Lightly and Leave No Trace.

Plan ahead and prepare, travel and camp on durable surfaces, dispose of waste properly, leave what you find, minimize campfire impacts, respect wildlife, be considerate of others, support local business and honor community, history and heritage. Help us keep Utah and Capitol Reef Country’s outdoor recreation areas beautiful, healthy, and accessible.